Stories of an African Choir II. Genesis

In the early 2000s, the Zaaiman family of Alberton, just outside Johannesburg, took possession of a new vehicle. They decided to celebrate the event that same evening and go out for dinner. Dad, Jannie, was driving; his wife, Marina, was in the passenger seat; two of their children were seated in the back. The family was looking forward to a joyful evening at a restaurant.

As they reversed down the driveway, a red bakkie stopped behind them. Jannie slowed down.

“I hadn’t even stopped yet when a group of armed youngsters approached the vehicle and demanded that we get out,” he recalls. “My blood ran cold. Without even thinking we got out of the car. My primary concern was for our safety.”

The boys demanded that Marina and their daughter, Anneke, should go with them. With a gun against Jannie’s head and his son thrashed aside, the driver of the red bakkie noticed a security vehicle on patrol in the distance and sped off, leaving the other four hijackers with the family. They pulled Marina and Anneke from the Zaaimans’ vehicle before jumping into it and speeding off.

“They didn’t even look old enough to be driving,” says Jannie.

The Zaaimans accepted the trauma of the hijacking as one of the downsides of living in South Africa. What really bothered them was the fate of the boys who had committed the crime.

“These were young men, probably not much older than our own children,” recalls Marina. “We tried to imagine the circumstances that could have led them to this point and decided we needed to do something. Surely there was some way we could help to bring meaningful purpose into the lives of young people growing up in our townships.”

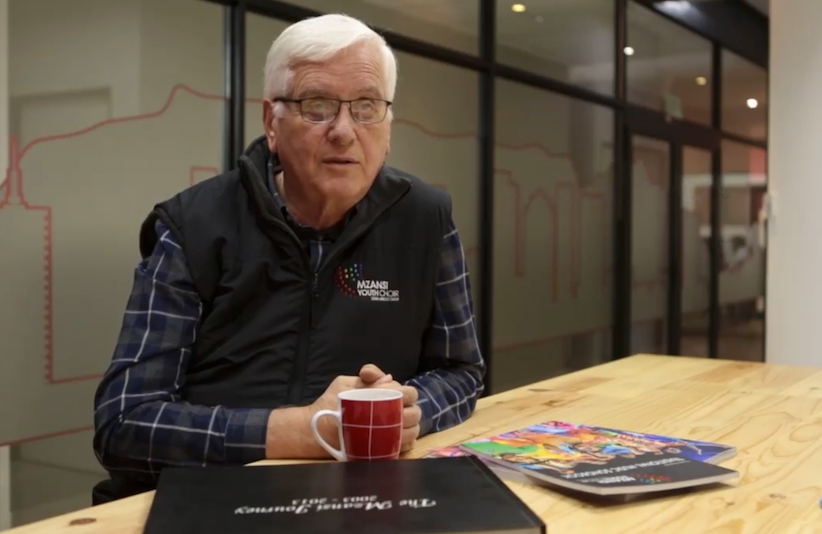

At the time, Jannie was chairperson of the Greater Alberton Education Forum. It occurred to him that with the exception of church choirs, there was no youth choir in the area. His children had been part of youth choirs when they were at school in the suburbs, but kids in the townships didn’t have the same levels of access. Being in a regional youth choir was not an option for them at the time.

Jannie called up the principals of schools in the townships around Alberton to pitch the idea of forming a regional youth choir in the area. They were, as he puts it, “ecstatic”.

On 26 July 2003, the Ekurhuleni Youth Choir (as Mzansi Youth Choir was known at the time) was formed, comprising 17 choristers from Tokoza, Katlehong, Vosloorus and Alberton. Jannie and Marina were paying the choir’s financial requirements from their own pockets. Henk Barnard graciously agreed to be the conductor and Franz Geldenhuys the accompanist. Within a year there were close to 70 voices in the choir, and Theo and Annie Veldsman had joined to assist.

“After 18 months we just couldn’t afford to keep it going like that any longer,” says Jannie. “Henk and Franz were working free of charge, which was not sustainable. We were paying for food, clothing, transport and quite a few other expenses for the 70 kids. After a performance that ended at say 11pm, we would have to get the choristers back to their homes all across the southern part of Gauteng, from Soweto via the south of Joburg to the East Rand.

“I remember one particular time dropping a kid off in the Johannesburg CBD at 4am and seeing people heading to Park Station to commute to work. By 8 o’clock I was sitting working in my office, completely exhausted.”

The Zaaimans would, at times, have choristers sleeping over at their home.

“Particularly over a weekend, if we had a performance that ended too late for us to take the children home, we would invite some of them to stay with us – those who didn’t live nearby. It wasn’t unusual to have more than 30 kids sleeping all over the house. I remember the second time this happened, we were awoken by a noise at 3am. ‘What is going on?’ we thought. I got up to investigate and found a group of girls heading towards the bathroom.

“’Why are you up so early?’ I asked them.

“’We are going to shower,’ they replied.

“’But why at this time of the night’

“’Because the last time we stayed over, the boys showered first and used up all the hot water. We wanted to beat them to it this time.’”

Although it was a tough time for Jannie and Marina, they learnt a lot through the process.

“You see the wonderful talent that these young people have, but without the means to reach their full potential,” says Marina. “Like the boy who walked more than 20km to choir practice in Alberton from Hillbrow – in slip-slops! That’s when you see the dedication. You see it in their eyes. They want to be somewhere, but they have absolutely no way of getting there.”

Jannie tells the story of Thabiso*, who lived with her brother in a shack after their mother passed on. She had no idea where who or where her father was. As a schoolgirl, she had nowhere else to go.

In time, her brother’s girlfriend moved in, and then their cousin from the Free State, and his girlfriend. In total there were five people living in that one tiny shack.

Despite these circumstances, Thabiso passed matric and got a bursary from an FET college.

“One of the other choristers came to us and told us that Thabiso simply couldn’t carry on living in the shack with four other people; she needed to focus on her studies,” Jannie recalls.

The choir found her a place to stay and sponsored her rent and food. Her marks shot up from the mid-50s to the mid-90s and she completed her diploma with distinction.

“While she was looking for work, we helped her to get her driver’s licence, which she passed first time,” says Jannie. “Through personal connections we got her a job at a marketing company. She phoned me one day to tell me that she had saved R8 000 to put a tombstone on her mother’s grave. To me, this represents extreme commitment to the memory of her mother, especially since she was so young when her mother passed away”.

“Another student chorister, Xoli*, asked me to come and see him in Tokoza – he had something to show me. When I got there I saw he had started a car wash. The lines were drawn and the structure was up, but no one was coming because he didn’t have shade net up.

“So we went and bought some shade net for his car wash – a relatively inexpensive investment, but one that made all the difference.”

Today Thabiso works for an engineering company and is doing exceptionally well. Xoli is washing 45 cars a week.

What does it cost to run a choir?

“About R1,5 to R2 million a year,” says Jannie. “All the money comes from donors – corporates and individuals looking to make a difference in society, and from the National Lottery.

“We have forged some amazing partnerships over the years, and are often overwhelmed by people’s generosity.”

For many companies, such as RMB, the relationship with the Mzansi Youth Choir is an opportunity to participate in the creative economy. Thanks to the support the choir receives it is able to pay stipends and salaries for the people who work to keep it going. It also covers the running costs of its three buses and two trailers, venue and sound equipment hire, annual events and outings for the choristers (choir camp, Christmas party, etc.), clothing for performances, and food – choristers get a meal at each rehearsal. The choir even provides toiletries, travel bags and clothes.

“For many it’s their only meal of the day,” says Marina. “It’s heartbreaking when a kid comes to choir and tells you, ‘I’m hungry because it wasn’t my turn to eat.’ And that is where we have seen a huge difference in the lives of our choristers and their families.

“Yes, on the surface the Mzansi Youth Choir is all about the music. But deep down, it’s about so much more.”

*not their real names

RMB PROUDLY PARTNERS WITH THE MZANSI YOUTH CHOIR BECAUSE

IT’S A BEAUTIFUL SOUTH AFRICAN STORY

* * * * *

Index

Stories of an African Choir – Transforming Lives Through Music

II. Genesis

III. Giving voice to the creative economy